- Home

- Sarah Selecky

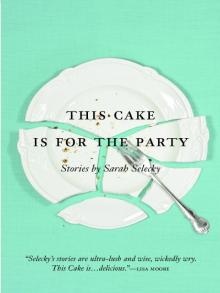

This Cake is for the Party

This Cake is for the Party Read online

Sarah Selecky grew up in Northern Ontario and Southern Indiana. Her stories have been published in The Walrus, Geist, Prairie Fire,The New Quarterly, and The Journey Prize Anthology. She earned her MFA in Creative Writing at the University of British Columbia and has been teaching creative writing in her living room for the past ten years. She currently lives in Toronto.

This Cake Is for the Party

THE STORIES IN THIS BOOK HAVE APPEARED

IN THE FOLLOWING PUBLICATIONS:

“Paul Farenbacher’s Yard Sale”

The Walrus, March 2010

“Prognosis”

Event, Winter 2009

“One Thousand Wax Buddhas”

Prairie Fire Magazine, Summer 2008

“This Is How We Grow as Humans”

The New Quarterly, Winter 2007

“Throwing Cotton”

The Journey Prize Stories 18, 2006,

and Prairie Fire, Summer 2005

“Standing Up for Janey”

The New Quarterly, Winter 2005

THIS CAKE

IS FOR THE PARTY

Stories by

Sarah Selecky

THOMAS ALLEN PUBLISHERS

TORONTO

Copyright © 2010 Sarah Selecky

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means – graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or information storage and retrieval systems – without the prior written permission of the publisher, or in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Selecky, Sarah Lucille

This cake is for the party : short stories / Sarah Selecky.

ISBN 978-0-88762-525-1

I. Title.

PS8587.E428T44 2010 C813'.6 C2009-907220-3

Editor: Patrick Crean

Cover design: Black Eye Design

Cover image: Michel Vrána

Published by Thomas Allen Publishers,

a division of Thomas Allen & Son Limited,

145 Front Street East, Suite 209,

Toronto, Ontario M5A 1E3 Canada

www.thomas-allen.com

The publisher gratefully acknowledges the support of The Ontario Arts Council for its publishing program.

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts, which last year invested $20.1 million in writing and publishing throughout Canada.

We acknowledge the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Media Development Corporation’s Ontario Book Initiative.

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP) for our publishing activities.

The author acknowledges the support of the Toronto Arts Council and the Ontario Arts Council.

10 11 12 13 14 5 4 3 2 1

Printed and bound in Canada

for ZZ

I am tremendously grateful to Zsuzsi Gartner for her unrelenting critical attention, support, and influence.

Thank you to Patrick Crean for his commitment and enthusiasm, to Janice Zawerbny for her diligence and care, and to Michel Vrána for his truly thoughtful design.

I am thankful for the fortitude of my literary accomplices: Julie Paul, Jessica Westhead, Heather Jessup, Erin Robinsong, Matthew Trafford, Laura Trunkey, Laure Baudot, Sarah Henstra, Scott Fotheringham, Mary Beth Deline, and Lesley Cowan. Thank you for your motivation, advice, and close reading. I owe a great deal to my teachers and classmates in the Optional-Residency Creative Writing MFA program at the University of British Columbia, especially Andrew Gray, Diane Fleming, Peter Levitt, Sioux Browning, and Susan Musgrave. Many thanks to all the women in the Salon in Toronto.

Thank you to Catherine Wright, Hilary Black, and Paulette Bourgeois, who allowed me to write in their quiet, beautiful spaces. Also to the Banff Wired Writing Program and the Humber School for Writers: these programs gave me the time and structure to write many problematic and necessary first drafts. Elisabeth Harvor read many of these stories in their early forms – thank you.

Thank you to Jason Dewinetz and Aaron Peck at Greenboathouse Books for the first This Cake Is for the Party.

To Tamara “Throwing Cotton to the Wind” Jakes, PD Bureau, and Usability Matters: thank you for patient, flexible employment while I wrote these stories.

A special thanks goes to my students, who continually inspire me with their practice.

Thank you to my mother, Mary Jane Selecky, for everything.

And a colossal cut of gratitude to Ryan Henderson for his legendary faith, encouragement, and love.

CONTENTS

Throwing Cotton

Watching Atlas

How Healthy Are You?

Go-Manchura

Standing Up for Janey

Where Are You Coming From, Sweetheart?

Prognosis

Paul Farenbacher’s Yard Sale

This Is How We Grow as Humans

One Thousand Wax Buddhas

All of you are perfect just as you are

and you could use a little improvement.

— SHUNRYU SUZUKI

Throwing

Cotton

This past New Year’s Eve, sitting on the loveseat in front of our little tabletop Christmas tree, I poured us both a glass of sparkling wine and told Sanderson: I think I’m ready to do it.

He kissed the top of my head and asked, Are you sure?

This is my last drink, I told him. I am officially preparing the womb.

Now it’s the May long weekend. Sanderson and I have driven four hours north to Keewadin Lake, a cottage that we’ve rented every long weekend in May since we were at Trent together. We share it with our friends: Shona and Flip, who have been married even longer than we have, and Janine, who found the cottage for all of us almost ten years ago. I have a stack of first-year composition papers that still have to be marked, but I left them at home so this could be a real holiday. I have a strong feeling about this weekend. I think this might be the weekend we conceive. I’m trying not to get my hopes up, but my instincts are usually good.

We get to the cottage late, nine o’clock. It’s already past dark and we’re all very hungry. I can smell tension between Flip and Sanderson like something electric is burning. They both retreat to the living room. It’s always been my job to sort the linens out when we arrive. But I feel particularly irritated that neither of our husbands has offered to help in the kitchen. These are progressive men. They know better than that. Shona and I move into the kitchen. Shona is an amazing cook, and she likes to do it.

Right in here, Shona says to me, even though I didn’t ask her anything. She digs out a yellow packet of spaghetti from the bottom of one of the boxes. Told you! she says. She also finds a pot with a lid, a can opener, and cardboard tubes of salt and pepper left over from the last people who stayed here.

A knife, she says, distracted. Were we supposed to bring our own knives?

I remember the drawer from last year and show her.

I don’t think they’re very sharp, I say. We should have brought a good one.

This will work, Shona says, and selects one with a plastic handle and a pointy, upturned blade. It’s not like we’re carving a roast, she says. She starts slicing cloves of garlic on one of the speckled stoneware dishes. Each time the blade strikes the plate, the sharp sound makes me wince.

The sun was down by the time we got here. Now it’s too dark to see anything. When I flick on the porch light, I disturb a fluster of moths. I cup my hands around my face and look out the window. There’s a

dock with a little motorboat tied to it and an apron-shaped beach. There is a pale glow that looks as if it’s radiating from the sand.

The linen closet is where it always is, in the main hallway. I pull out musty-smelling sheets and threadbare pillowcases for both of the beds upstairs. For Janine’s bed, on the main floor, I pick out the pink and orange flowered ones. Janine loves colour more than anyone I know. She’s a graphic designer, but at Trent she studied English Lit like the rest of us. Not counting Sanderson, of course. She was actually enrolled in Sanderson’s drawing class in her second year, but she withdrew when I told her I was sleeping with him. Those first years with Sanderson were more awkward than I like to remember. Our age difference was much more shocking when I was twenty-two years old. Now I’m teaching English at Ryerson and he’s moved to the Art History department at York and I can’t remember the last time I felt scandalous. I drop the flowered sheets off first, leave them folded on the edge of the mattress in her room.

She’s not coming, Flip calls to me when he sees me there. Didn’t she call you? I told her to call you.

She didn’t call me. I hug my chest and follow his voice into the living room. I look back and forth between Flip and Sanderson. Janine didn’t call, did she, Sand?

He shakes his head and fills his glass with more wine. Did she say why?

She said she had a family thing.

I started dating Sanderson two semesters after I finished his class. I was the one who asked him out. We met in East City, across the river, at a small café not far from the Quaker Oats building. There was a woman wearing a red apron who served us coffee in thick white cups. I put two packets of sugar in my coffee and a long dollop of cream. He told me, You have a good eye. But you need to trust the line when you draw. He had silver strands of hair at his temples. I thought this made him look debonair and sophisticated. Now I think it’s safe to say he’s going grey.

I wish you wouldn’t drink so much this weekend, I tell him.

We just got here, he says. It was a long drive.

Flip is stretched out on the chair, even though the chair itself doesn’t recline. His body is slouched down so his seat reaches the edge of the cushion and his head is pressed into the back of the chair. His long legs are crossed at the ankles. It doesn’t look comfortable. He takes up most of the living room.

I can tell you why she’s not here, Sanderson says to me.

He rubs the side of his sandpaper face with one hand. He hasn’t shaved for three days. He says the stubble makes him feel like he’s having a more authentic cottage experience, so he cultivated it before we arrived. His beard is still dark—there’s a patch of grey on his chin, but the rest of his face still grows a mix of dark reds and browns. Earlier this week, watching him sleep, I picked out the different colours sprouting. They grew like a pack of assorted wildflower seeds.

Janine feels threatened by your choice to have a child. She’s withdrawing from you so she doesn’t feel— He trails off.

Lonely and misguided, hopeless, bitter? Flip finishes for him.

Exactly, says Sanderson. She doesn’t want to feel threatened.

Wait. My choice to have a child?

Flip ignores me. I can see now that he is stoned. But, but, he says. Janine must feel lonely and threatened already. Otherwise she’d be here, right? Whoa. I think that’s a paradox.

Did she tell you that?

No, says Flip, looking at me again. I think it was her grandmother’s birthday.

I glare at Sanderson. He looks pleased with himself.

The sound of the knife cutting on stoneware stops. I go back into the kitchen to open a bottle of seltzer. My choice to have a child. Okay. What I really want is a glass of red wine. Sanderson, of course, has the whole bottle next to his chair.

Shona hands me a glass from the cupboard above the sink. You want some lemon?

I want what you’re having. I look at her glass of wine on the counter. But yes. Thank you. Lemon.

Shona is getting her master’s degree at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education at the University of Toronto. She has told me stories about the kids she’s working with in her practicum. For instance: There is a boy who is obsessed with chickens. He calls himself the Chicken Man. Occasionally he clucks to himself when he is drawing at his desk. When he’s excited, he calls out, Chick-EN!

Shona has this quality. She observes the world more carefully than I do. She is slow to make decisions or judgments. She will listen to you ramble, and when you are finished, you feel like she has just told you something important about yourself. She is going to be a remarkable teacher. I hope that my son or daughter will be able to study with her.

Shona slices a lemon in half and squeezes it over my glass. Have lots, she says, it’s cleansing. She rinses her hand under the tap, blots it with a dishcloth. Cloudy tendrils of lemon juice work their way into the water. I can hear the fizz of small bubbles rising and breaking the surface.

I look up. Did you know Janine couldn’t come this weekend? I ask her.

Flip told me. Birthday party? Something.

I think it’s strange. That she didn’t call me.

Shona doesn’t answer. She reaches up and pulls her ponytail apart to tighten it and I catch a whiff of lacy, pungent garlic. Her oval face with all the hair pulled back is like an olive.

I say, Sanderson says Janine got her dog because I decided to have a baby.

She was looking into the breeders before that.

Yes, but. She didn’t actually get Winnie until after I told her.

And Sanderson thinks this is important.

I look into my glass and focus on the bubbles that cling to the sides.

There’s never the perfect time to have kids, I say. Right? You just have to jump right in. You never feel one hundred percent.

You make a convincing case for it, Shona says.

Janine’s latest project is a font that she’s made entirely out of pubic hairs.

I’m still working on it, she said on the phone the last time I spoke to her. Parentheses were easy. But I need an ampersand. I haven’t even done upper case yet.

I could hear a reedy whine from Winnie in the background. Then she said, I was sitting on the toilet one day and I saw a question mark on the tile by my foot. The most perfect question mark.

In your pubic hair, I said.

It’s important for me to keep the letters genuine. I don’t want to mess around with the natural curls.

Right. That would be missing the whole point.

No! Off! Mama’s on the phone right now! Janine said. Anyway. I think it looks good. Almost Gothic, but still organic.

I wish that I could be more like Janine. She doesn’t even pretend to care about anything other than herself, and we all love her anyway. I shouldn’t be so surprised that she didn’t call me about this weekend.

Wait a minute, Shona says in the kitchen, raising her wineglass and pointing at it with her other hand. Where’s the rest of this? Is Sanderson hogging the wine?

In the living room, Flip and Sanderson have started to argue.

Sanderson leans forward in his chair in a half-lunge. His white sweatshirt has a logo with two crossed paddles on the chest, and a few spots of red wine that he won’t notice until tomorrow morning.

Flip’s face is tight. He says, If smokers came with their own private filtration systems, they could breathe what they exhale themselves. But we haven’t invented that yet. So we stop smoking in bars.

Nobody’s forcing you to breathe smoke.

Yes they are. In a bar, when there are smokers, it’s everywhere.

Sanderson nods his head, leans back in the chair. Listen, he says. If I don’t want to see a monster truck derby, I don’t go to the arena. Get it?

You don’t have to be an asshole.

You used to be a smoker too. I don’t see where you get off.

Shona interrupts. Honey, leave it, you’re stoned. Sanderson, pour me some wine.

Marijua

na is different, Flip says.

They’ve been smoking in bars since the beginning of time, Sanderson mutters into his glass.

I don’t like to see them fight like this. Sanderson thinks Flip needs to stop smoking dope—that it’s making him dumb. Shona told me that Flip cringes when he reads Sanderson’s emails because of the spelling errors. It’s so important to each of them that the other appears intelligent. As though Sanderson’s own intelligence is threatened when Flip appears dim-witted, or the other way around.

I get the bottle myself, since he’s not making any move to do it. I pour some for Shona. Then I pour the remaining trickle into Flip’s glass. Shona made dinner for us, I say, and turn to Sanderson. Say thank you.

Don’t talk to me like I’m a child, he says. Then he flashes a wine-stained smile at her. Thank you, Shona.

There was a student in the fall semester. A young woman named Brianna. She’s very bright, Sanderson told me. Her technique is rough, but inspired. Sanderson would call me in the afternoon, sometimes as late as five o’clock, to tell me that he was going to miss dinner. He never lied about where he was. He’d say they were going for drinks, grabbing a bite. He was helping her with her portfolio. One night he took her to Flip’s bar. That’s how self-assured he was. Flip told me that he saw them share a plate of calamari. That the woman fed him a ring from her fork. He said, The way she leaned across the table, Anne. I don’t know.

I have always known this about Sanderson. He’s one of those men who can keep his loving in separate compartments. He can love two women at once and not feel that he’s betraying either of them. But when we got married, we promised that we’d tell each other about our attractions, that there wouldn’t be any secret affairs. I can understand having a crush. It’s lying about it that bothers me.

It’s eleven o’clock when we sit down at the wobbly kitchen table to eat. The pasta should have been cooked for another five minutes. It sticks to my teeth like masking tape. But the four of us are so hungry we finish most of the noodles anyway, use up the whole pot of sauce to cover the piles on our plates. Flip mops up the last of it with a slice of garlic bread. Sanderson is quiet, possibly craving a cigarette. Shona is the only one who has wine left in her glass. I wrap my ankles and feet around the cold metal chair legs and silently will Sanderson to not open another bottle. It’s cold in the cottage, even though the candles on the table make it look cozy. I could go put on some socks, but Sanderson already took my bag upstairs and I’m too lazy to go up there. My belly feels full and tight from too much pasta and bubbly water.

This Cake is for the Party

This Cake is for the Party